Lessons in Coping With Scarcity and Uncertainty

All animals — humans included — are creatures of habit. We have our routines, our favorite places to go for food, our home maintenance practices, our bedtime rituals.

Often these are layered and nuanced — some people might go grocery shopping every night after work, while others go only once a week — but the point is, we design routines that work for us: based on where we know resources to be, we can get our needs met at every level.

When those routines get turned upside down, whether because of a job loss, an illness or death in the family, because we moved, or even a pandemic — we become stressed. We still have needs, but getting them met becomes another thing we have to think about.

In the early weeks of COVID-19-related self-isolating, for example, we saw shortages as people hoarded paper and food products. Likely, this was the result of people not wanting to have to think about meeting their needs in the stressful times ahead.

Of course, the knock-on effect was that their actions forced routine changes for a lot of other people. Stores had to limit the number of packages people could buy, and many of us shifted our schedules so we could shop earlier in the morning, as soon as stores opened, to be sure we could find what we needed.

What does this have to do with a book about raccoons?

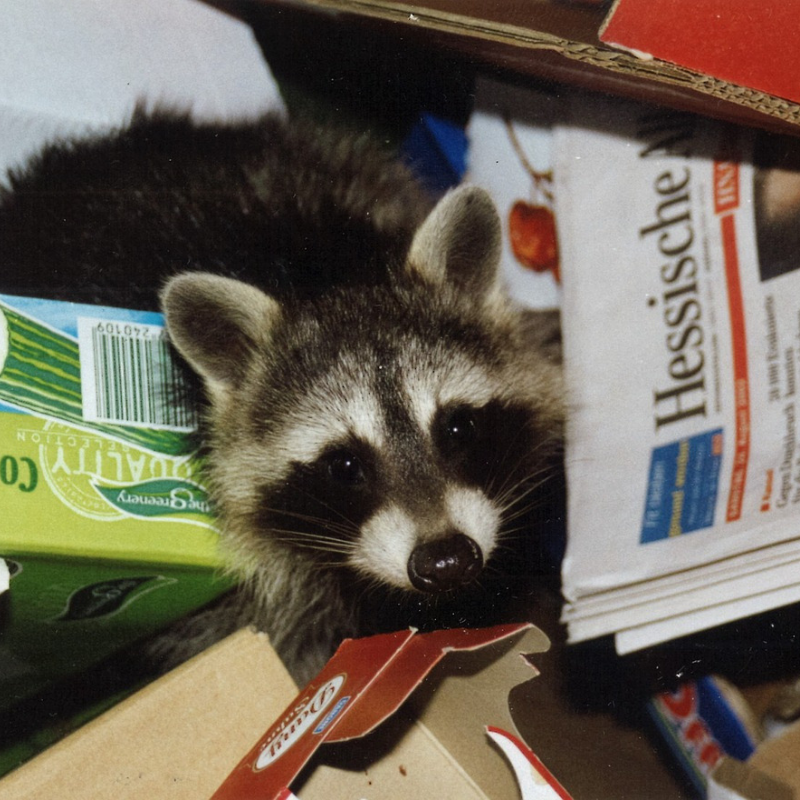

Wild animals have their routines, too. Species like raccoons, which live and travel within well-defined “home ranges,” have their go-to spots for food, water, shelter, and even toileting. They mark their paths of travel by rubbing against them, leaving behind a scent signature that helps guide them even when they have poor eyesight.

In the book, all this gets upended when humans come along and destroy the animals’ habitat. There’s a moment of saving grace when Roxy, Rufus, and Renae recognize their favorite berry bush, and when they’re able to use it as a landmark in the little bit of woods that hasn’t been destroyed.

Until that point, though, they can’t find their familiar scents. Nothing looks as it did before. They aren’t even sure whether they’ll be able to find more berry bushes. They’re lost and alone and scared — much like we humans might have felt upon seeing that stores were completely out of chicken or beef, or hearing that we wouldn’t be able to go to our favorite places for the foreseeable future.

Lessons about adaptation and resilience

The book isn’t a perfect parallel. For one thing, the kits don’t have to practice social distancing when they befriend another raccoon family, or when they dine alongside other species at communal backyard food dishes.

(In fact, diseases like canine distemper virus spread like wildfire throughout animal populations precisely because they don’t know to change their routines to practice social distancing. This is an even higher risk, as it is for humans, among dense populations — for instance, when animals have been forced together into tighter habitats.)

What the book does show is the need to help each other out when we’re in trouble. Roxy, Rufus, and Renae don’t just befriend the other raccoons — they help another mom and kit out of a bad jam. In turn, they’re helped out of their own jams.

There are always options, in other words. They may be suboptimal, but they exist. We just have to be willing to see them.

A word about “trap and release”

These are all reasons why the “trap and release” method of wildlife control is not as humane as it’s assumed to be. Think about the last time you moved house. While you have guaranteed shelter, it probably took you a few weeks to get to know your new environment: the closest grocery stores, the easiest ways to get there, the fastest route to your workplace or school.

As you get to know those routes and locations, you make mistakes. You get in the wrong turning lane, or you accidentally cut off another driver. You arrive at a store to find its hours are different from the ones Google lists — or it’s open, but the aisles are all different from the maps your brain is familiar with.

These are all minor and somewhat embarrassing inconveniences, but in the wild, similar obstacles can be a life-or-death battle for survival. The other drivers you annoy with your lack of knowledge? In the wild, they’d be considered the area’s dominant species. Your fumbling around with your commute, schedule, or store aisles would make you prey.

We’re coming up on the holiday season, so my request is this: if you have a small animal sheltering in your home or yard during cold weather and you don’t want them there, please consider compassionate, humane solutions like eviction and exclusion. You can use a few easy, inexpensive tricks to show animals they’re not wanted, and they’ll be on their way — most have alternate den sites set up around the neighborhood!

If you must call a wildlife removal expert, find ones who practice eviction, exclusion, and — when they happen to have separated mothers and babies — reunion. Two Canadian companies, Skedaddle Humane Wildlife Control and AAA Gates Wildlife Control, are a shining example of what questions to ask the companies you call to be sure they’re really humane. And you’ll be a shining example of what compassion really looks like.

Like what you're reading? Subscribe to get an email whenever I publish, or leave me a tip!

Member discussion